Are you ready to rock?

As first experiences go in buying records it’s not the best, and sadly the pattern is repeated when I reach secondary school and buy my first LP. I go into the newsagents in Market Place in Pocklington. Upstairs they have a fairly comprehensive selection of today’s poptastic releases.

It’s 1971, I’m fourteen, and it’s time I bought my own proper record. I need a rock record, not a novelty one – I’ve left Val Doonican at home – not only because the other boys are a bit pissed off with me listening to their records on the common room record player, but because I have to make a statement about the kind of person I am. That’s what albums are about, surely? Your album collection defines who you are.

There are four boarding houses at the school and they each have their own house style: Gruggen are into west coast, country rock stuff – The Eagles and Buffalo Springfield; Hutton are into psychedelic rock – Jefferson Airplane and Tangerine Dream; Dolman are prog – Emerson, Lake & Palmer and King Crimson; and Wilberforce, my house, are doggedly into 4/4 rock – Free and The Who. Tellingly, each of the four houses claims David Bowie as one of their own.

But my task is to find an album that shows I’m a) a loyal member of my tribe, and b) a tasteful individual.

I find a Rolling Stones album I haven’t seen before: Gimme Shelter. One that hasn’t been seen before? That’s going to be really good for my street cred, isn’t it? Imagine turning up with a new Rolling Stones album.

Hang on, it’s got songs on it I already know: ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’, ‘Honky Tonk Women’, ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’. This makes me slightly suspicious, so I ask the guy behind the counter to put it on the shop record player to make sure there’s nothing wrong with it. Maybe it’s one of those Top of the Pops albums from the Hallmark series where all the tracks have been covered by some sound-a-like session musicians? He puts on side one – it sounds like The Rolling Stones, it is The Rolling Stones, it sounds great.

I read the back of the album cover – it tells me that these are some of the tracks featured in their Gimme Shelter film, and that side two captures the Stones in concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall. The Royal Albert Hall? Royal? You can’t get any better than royal, can you? At the bottom of the blurb it says: You’re holding an LP by the greatest Rock ’n’ Roll Group in the World! Why aren’t you playing it?

Fair enough.

‘I’ll take it!’ I shout.

I rush back to school and the common room and put it on. Everyone is impressed – I think I may have defined myself – though one of the real aficionados points out that all the songs on side one have already been released as singles, or on previous albums like Beggars Banquet and Let It Bleed. He says it’s a bit like a greatest hits album which is a bit naff. But he also says side two is a more unusual collection of songs. So I turn the record over. It begins to play . . .

It’s an absolute disaster.

I knew it was live – it was recorded at the Royal Albert Hall for Christ’s sake – but it appears to have been recorded in front of thousands of adoring female fans, and they scream through the whole bloody thing. They don’t even scream at moments of high emotion, like Mick wiggling his hips, or points of musical significance, or the ends of songs, they just scream constantly at the same pitch for the full twenty minutes. The aficionado pipes up: ‘You might as well go and suck Marc Bolan’s knickers.’

Even though I secretly like Marc Bolan I realize this is a damning verdict and that I may never be cool.

It’s the rule that you can’t take records back to the shop just because you don’t like them because they’re afraid you might have scratched them, or gouged out the grooves with a stylus that’s too heavy. And if they’ve played it to you in the shop you can’t complain that it was scratched. So I’m stuck with it. And in fact I’m still stuck with it. It is still in my record collection. I have roughly five hundred vinyl albums and it’s still there. The first one. I’ve just played side two again for the first time since 1971. It’s as mind-numbingly awful as I remember. This is why The Beatles stopped touring – crappy PAs and so much screaming you can’t hear the music. But I still have it because, as I said, your albums define who you are, and this mistake is part of who I am. I will not throw it out, but having owned up to it I feel some catharsis.

Our school house is called Wilberforce House – it’s named after a previous pupil, William Wilberforce, the bloke who helped to stop slavery. Unfortunately his teachings haven’t reached the house named after him, because at Wilberforce fagging is still in operation.

I’m a fag for one of the prefects. I clean his shoes. I make his bed. I make him toast whenever he decrees. I fetch and carry, and deliver messages. I go to the newsagent and buy his porn mags for him. It’s not quite slavery because at the end of every term he gives me a ‘tip’.

And at the end of his final term at the school he sells me his guitar. I have a guitar. This is progress!

Dad has such disdain for this instrument of the people, this instrument of pop and of protest, that he disparagingly calls my guitar a ‘banjo’ – the banjo being the lowest of the low in his opinion. Years later when I buy an actual banjo he doesn’t know how to refer to it.

At the end of one term when Dad’s briefly in the country he picks me up from school, and as I try to put my guitar in the back of the car he says: ‘I’m not sure we’ve got enough room for your banjo.’

At home he makes such a display of watching me fumble about as I try to make chord shapes – tutting and rolling his eyes – that I never take it home again. I leave it at the school, or send it home with another boy if he’ll have it.

What is this guitar?

It’s very cheap. For a reason. It has the action – the distance between the strings and the fretboard – of one of those egg slicers advertised on the telly in the early seventies. As I try to push the strings down to make chords it tries to cut my fingers into sandwich-friendly slices. And it probably sounds like someone strumming an egg slicer as well. But it is mine, all mine.

Strings are prohibitively expensive. A new set of strings will set me back more than I’ve paid for the guitar. I can’t afford that, so the cuts in my fingertips get filled with rust. But after a month I can play ‘Banks of the Ohio’ – a current top ten hit for Olivia Newton-John – without crying out in pain too often. It’s not only a fine murder ballad sung by a girl who’s the subject of many an idle daydream, it’s also a three-chord wonder: A, E and D.

The three easiest chords.

With these three chords I can play – to varying degrees of similitude – ‘Whole Lotta Love’ and ‘Rock and Roll’ by Led Zep, ‘Not Fade Away’ by The Stones, ‘Johnny B. Goode’ by Chuck Berry, ‘Wild Thing’ by The Troggs (and Hendrix), ‘I Can’t Explain’ by The Who, and ‘All Right Now’ by Free.

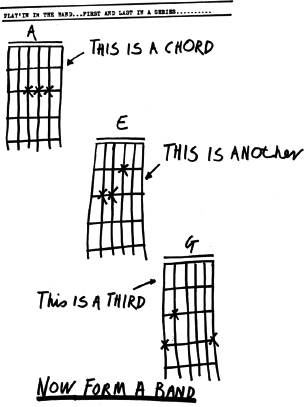

Five or six years later a guy called Tony Moon will draw three chord shapes on a piece of paper and put them in his fanzine Sideburns. Beside each shape he will write: This is a chord. This is another. This is a third. And underneath he will write NOW FORM A BAND. This is supposedly one of the seminal moments of the punk movement, but I would humbly suggest we were already aware of this back in 1971.

Also, the three chords Tony Moon drew were A, E and G. And G is a shape I won’t master for another year – I have to stretch my third finger so far back from my first and second fingers that any slip-up and I’ll end up guillotining my hand on the old egg slicer. I then learn how to form a barre chord by laying my first finger across all the strings and bending the other fingers into an E chord in front of this ‘barre’. I can slide this shape up and down the fretboard and play all twelve major chords with it. By lifting my third finger, the shape becomes a minor chord and sliding it up and down again I now have all twelve minor chords. Twenty-four chords with one basic shape – I now have access to more or less every song I’ve ever heard. This is like finding the Rosetta Stone. I can play anything I want, and I want to play ‘Paranoid’ by Black Sabbath, and ‘Smoke on the Water’ by Deep Purple.

Ritchie Blackmore, the guitarist from Deep Purple, is particularly obliging for wannabe players like me – he uses barre chords on nearly every song. I reckon that if I could get a guitar with a lower action – one on which I could fret the chords properly instead of sounding like a plinky-plunky washboard – an electric one, with an amplifier, and if I could get a drummer, and a bassist, and a singer, and if I could write some really good songs . . . I could easily have a band like Deep Purple. I could be an international rock god.

Luckily for me there’s already a band in Wilberforce House – well, the beginnings of a band – but the guitarist role is already taken by a boy called Iain. He’s got an electric guitar, a Gibson Les Paul like Paul Kossoff plays in Free, and he’s roughly a hundred per cent better at playing it than me. He can play the intro to Led Zep’s ‘Stairway to Heaven’, and get this – he can almost play without looking at his fingers!

Another boy with the same name but different spelling, Ian, is on the drums. I heartily applaud any parent with the generosity of spirit to give their child a drum kit. Pop music would be nowhere without them. Drumming is something you need to start early. Thankfully Ian’s parents are these kind of people and he’s already been playing for years. He sounds like the real thing.

The only negative thing about this nascent band is that they’re both a bit shy. The guitarist/singer in particular. The first time I’m allowed to watch them I squash into the tiny piano practice room: it contains a piano, Ian and his drum kit, Iain with his guitar and amplifier, and as many boys as can squash into the available space; five or six of us crammed into one of the corners and sitting on top of the piano.

They play ‘All Right Now’ which has a very distinctive drum pattern and guitar sound. It sounds like the actual record! However, Iain the guitarist is facing the wall. This isn’t because there’s no room, it’s because he’s nervous in front of people. And when the point arrives for the vocal to come in . . . nothing much happens. Iain is also the vocalist, but he doesn’t let rip like Paul Rodgers, he just mumbles into the wall. He has a PA of sorts – a mic plugged into the spare socket on his guitar amp – but even with that we can’t really hear him.

I come away from this three-minute ‘gig’ with a plan: I’m going to be in this band. And I’ve worked out a way of doing it – I’m going to get a bass guitar. Surely anyone can play bass, it’s just one note at a time, how hard can it be? If you listen to a lot of sixties and seventies rock you’ll find that quite a lot of people had this idea; for every inventive bassist there are ten others who do nothing more than play the root note of each chord. I think it’s the accepted ‘easy’ way into a band.

So how do I get a bass guitar? I’ll buy one, obviously – but where do I get the money?